By Emelia Allan

“I know this not only because the research says so, but because of my own experience as a Ghanaian woman…”

May 6, 2015. As a member of the Kassena-Nankani ethnic group in Ghana, I grew up seeing my cousins and other girls suffer the pain of female genital mutilation (FGM) and forced marriage too often and usually against their will. Although they detested these acts, not submitting to them would have meant being stigmatized and living with the fear of remaining unmarried.

I vividly recall witnessing the abduction of my older cousin. We were at the market when she was grabbed by a group of young men who wanted to force her into marriage. In her attempt to free herself, she was hurt so badly that she died a few days later. The only reason why I escaped this harm was because my father never supported these acts.

Child marriage is a common harmful traditional practice (HTP) in my country. Harmful traditional practices such as FGM and child marriage cause a disproportionate amount of violence against girls and perpetuate traditional notions about female inferiority. I know this not only because the research says so, but because of my own experience as a Ghanaian woman and my work as a child protection officer with UNICEF.

The most widely practiced HTPs in Ghana are child marriage, marriage by abduction, FGM, and ritual servitude (trokosi).[1] Marriage by abduction, wherein girls are pressed to marry men who have carried them off by force, is still largely practiced in communities within the Upper East and Upper West Regions, while trokosi, a custom that involves the ritual servitude of girls, is practiced in some southeastern communities of the Volta Region. [2] As recently as 2013, there were between 4,000 and 6,000 women and children under bondage as trokosis in Ghana.[3] And despite strong legislation against FGM, the national average remains at about 4 percent, with prevalence as high as 16 percent in the Upper West region.[4]

The most prevalent HTP in Ghana is the marriage of children. The practice is explicitly criminalized in the Children’s Act of 1998. And yet, with current figures at 27 percent, Ghana continues to have one of the world’s highest child marriage prevalence rates – one girl out of every four! Not surprisingly, there are more child marriages in rural areas than in urban ones, with significant variation across regions.[5] And there is a clear correlation between poverty, low education levels, and the likelihood that a girl will be married before age 18.

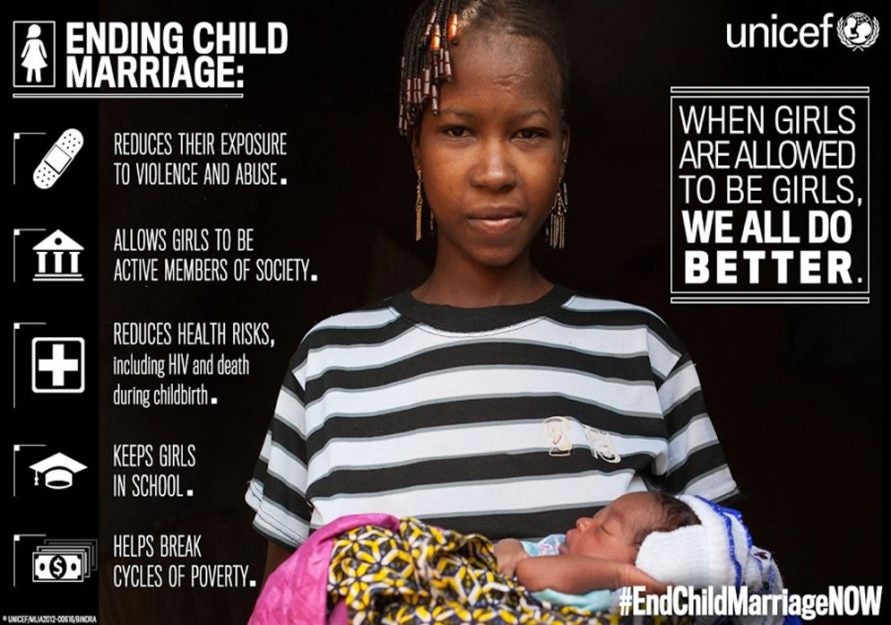

Indeed, child marriage has tremendous implications for the development of girls and for societies. Its effects are multidimensional, driving girls into a cycle of poverty, poor health, illiteracy and powerlessness. Child marriage undermines nearly every Millennium Development Goal; it is an obstacle to reducing poverty, achieving universal primary education, promoting gender equality, improving maternal and child health, and reducing HIV and AIDS. In short, child marriage is an infringement on the right of the girls to their dignity and freedom.

The United Nations Population Fund estimates that 407,000 girls born in Ghana between 2005 and 2010 will be married before age 18 by 2030 unless urgent action is taken.[6] Following intensive campaigns and work by government and non-governmental organizations, Ghana has seen some progress, particularly in the legal area, where there is a framework to protect women and girls against these practices. Nevertheless, we are a long way from zero tolerance. To get there we need to apply a multipronged approach that ensures the active engagement of all relevant stakeholders, including traditional and religious leaders.

The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection has an Anti-Child Marriage Unit tasked with combating child marriage and other HTPs. This is a step in the right direction. With support from UNICEF and other donor agencies, including the Dutch Government, the ministry will establish a national strategic framework while coordinating mechanisms for eliminating child marriage and increasing preventive action by traditional leaders, religious bodies, and communities.

The program will also seek to increase public response to taking action against child marriage through communication for social change. An integrated approach involving traditional and religious leaders in tandem with the media is a key component that should help pave the way for tackling other harmful practices.

I believe that people will change their behavior when they understand the effects and indignity of harmful practices and when they realize that it is possible to give up harmful practices without giving up meaningful aspects of their culture. Culture is, after all, not static but always adapting and reforming.[7]

[1] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], Human Rights Council (2008, Feb.). (A/HRC/7/6/Add.3)

[2] The Ewe word trokosi means “slaves of the gods.” In this practice a girl is handed over to a priest by her family in servitude. She becomes his property and is made to carry out chores such as cooking, washing, farming, and fetching water. Ame, R. K. (2013). “Traditional Religion, Social Structure, and Children’s Rights in Ghana: The Making of a Trokosi Child.” In Vulnerable Children, pp. 239-255. New York: Springer.

[3] Mistiaen, V. (2013). “Virgin Wives of the Fetish Gods – Ghana Trokosi Tradition.” Website article. Thomson Reuters Foundation.

[4] UNICEF (2013). Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. New York: UNICEF.

[5] Ghana Statistical Service (2011). Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (with An Enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker).

[6] UNFPA. http://ghana.unfpa.org/assets/user/file/ChildMarriageProfileGH.pdf

[7] World Health Organization (1996). Female Genital Cutting: A Joint WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA Statement.

![]() Emelia Allan is a UNICEF child protection officer based in Ghana and a Spring 2015 G. Barrie Landry fellow at Harvard FXB.

Emelia Allan is a UNICEF child protection officer based in Ghana and a Spring 2015 G. Barrie Landry fellow at Harvard FXB.