By Victoria Fan, Bradley Chen, and Arlan Fuller

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads . . .

. . . defend you

From seasons such as these?

—Shakespeare, King Lear, 3.4, lines 1831-35

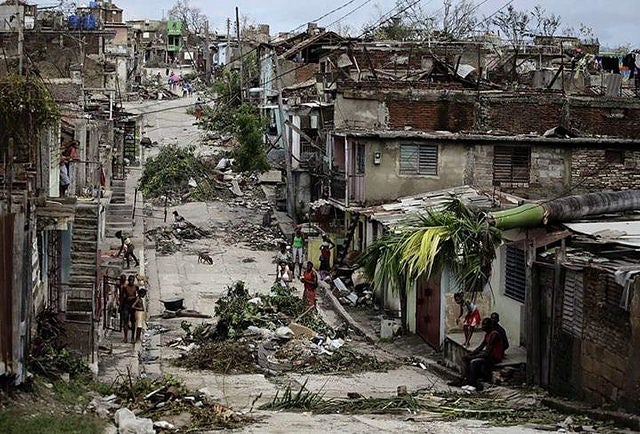

Hurricane Matthew stormed through Haiti on October 4, killing hundreds and leaving many others without shelter. Hurricane Matthew struck, even as Haiti has struggled to recover from the 2010 earthquake and the devastating cholera outbreak which followed. As FXB Center Director Jennifer Leaning remarked the events of 2010 were appropriately “called an apocalypse: a catastrophe, a cataclysmic event.” In recent days, Haitians took to the streets to protest a weak humanitarian response, an act of desperation resulting in the looting of several U.N. trucks for food and supplies. Those affected by the hurricane have many urgent humanitarian needs, with food and clean water being the most urgent. Yet also on that list of needs is housing. A recent New York Times article found that several hundred Haitians have resorted to staying in caves as their only shelter—many defenseless “houseless heads” indeed.

Just how important is housing for health in Haiti? In a recent paper, we (Fan and Chen, with Halliday) identified housing arrangements after the earthquake as a significant determinant of infant mortality. Households living in post-earthquake camp shelters have higher child mortality than those displaced, yet not living in camps.

Child mortality risk is higher for those in camps although in theory they have better resources available than displaced people living outside of camps. Those living in camp shelters may be getting services of inadequate quality or otherwise may face challenges such as violence unmeasured by our survey data. Despite better access to food, water, bed net use, and vaccines, children in camps still have worse health than other migrant and displaced households. Those reasons need to be better understood.

We also find that those who do not (or cannot) move to camps or elsewhere, are quite vulnerable. The child mortality rate for households who stayed in place after the earthquake was similar to those in camps. These populations are literally ”left behind.“ Efforts are needed to identify vulnerable populations to provide focused assistance after any disaster –including Hurricane Matthew. In a September 2016 tally by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), there were still fifty-five thousand individuals who had been displaced to post-earthquake temporary shelter and were still living there, six years on after the earthquake.

There has been talk of how the donor community can help (or at least not harm) the Haitian community. FXB fellow Satchit Balsari and his co-authors commented in 2010 on the critical importance of protecting children who have lost their parents and homes and the challenges of settlements of displaced people. Colleagues at the Center for Global Development (CGD) have advocated for donating cash rather than material goods as well as moving to a catastrophe-insurance model from the current model of disaster aid. No doubt these are all valuable suggestions.

In my own (Fan’s) field visit to Haiti, specifically to a community financed by individual donations and built by the Red Cross in Taiwan, there were reports that getting building materials and supplies into the country was a major and persistent challenge. With significant transportation, logistical, and procurement barriers, rebuilding is difficult. To rebuild, Haiti will need not only financial resources but human resources. Haiti needs capable people—city planners, architects, builders, public health engineers, health and housing specialists—to design, procure, and build sturdy and secure housing—houses that defend Haitians from seasons as these. CGD also stresses the importance of partnering with local organizations with a long-term presence on the ground for these kinds of efforts.

Victoria Fan is an assistant professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and an FXB fellow in the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights. You can follow her on Twitter at @FanVictoria. Bradley Chen is an assistant professor at National Yang-Ming University (Taiwan). Arlan Fuller is a research associate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the executive director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights.

Photo of Haiti after Hurricane Matthew, courtesy of European Union Delegation to the Republic of Haiti, through a Creative Commons 2.0 license