Raising the bar: The need for high-quality healthcare for incarcerated youth

By Tess Kelly, LLB, BA, MPA

Children in the criminal justice system have complex physical and mental health needs that are often exacerbated by incarceration. [1] These needs are too often ignored, and there is a dearth of publicly available data on health systems, governance, access to care, and service delivery in detention settings.[2] To help fill this gap, with the support from the FXB Center’s Structural Racism Initiative for Diversity with Equity (STRIDE) grant, I partnered with Citizens for Juvenile Justice (CFJJ) to explore issues relating to healthcare access and quality for incarcerated youth. As part of this work, along with co-authors Joshua Dankoff (CFJJ) and Dr. Elizabeth Barnert (UCLA), I recently published a paper in Pediatrics examining and comparing medical care standards for incarcerated youth across the United States.

This work built on my previous FXB Center research analyzing global minimum standards for healthcare of children deprived of their liberty. I also drew on my experience in Australia, where I worked alongside Aboriginal community-controlled health providers, community leaders, and families, advocating for the health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in custody. That work reinforced what decades of research confirm: many children enter custody with profound unmet health, mental health, and developmental needs, often rooted in racial inequities and systemic failures that impinge on their lives long before incarceration. I also saw firsthand how comprehensive, culturally safe, and coordinated care can be life changing. This led me to the conclusion that high-quality care in detention to identify and address unmet needs should be the norm and not the exception.

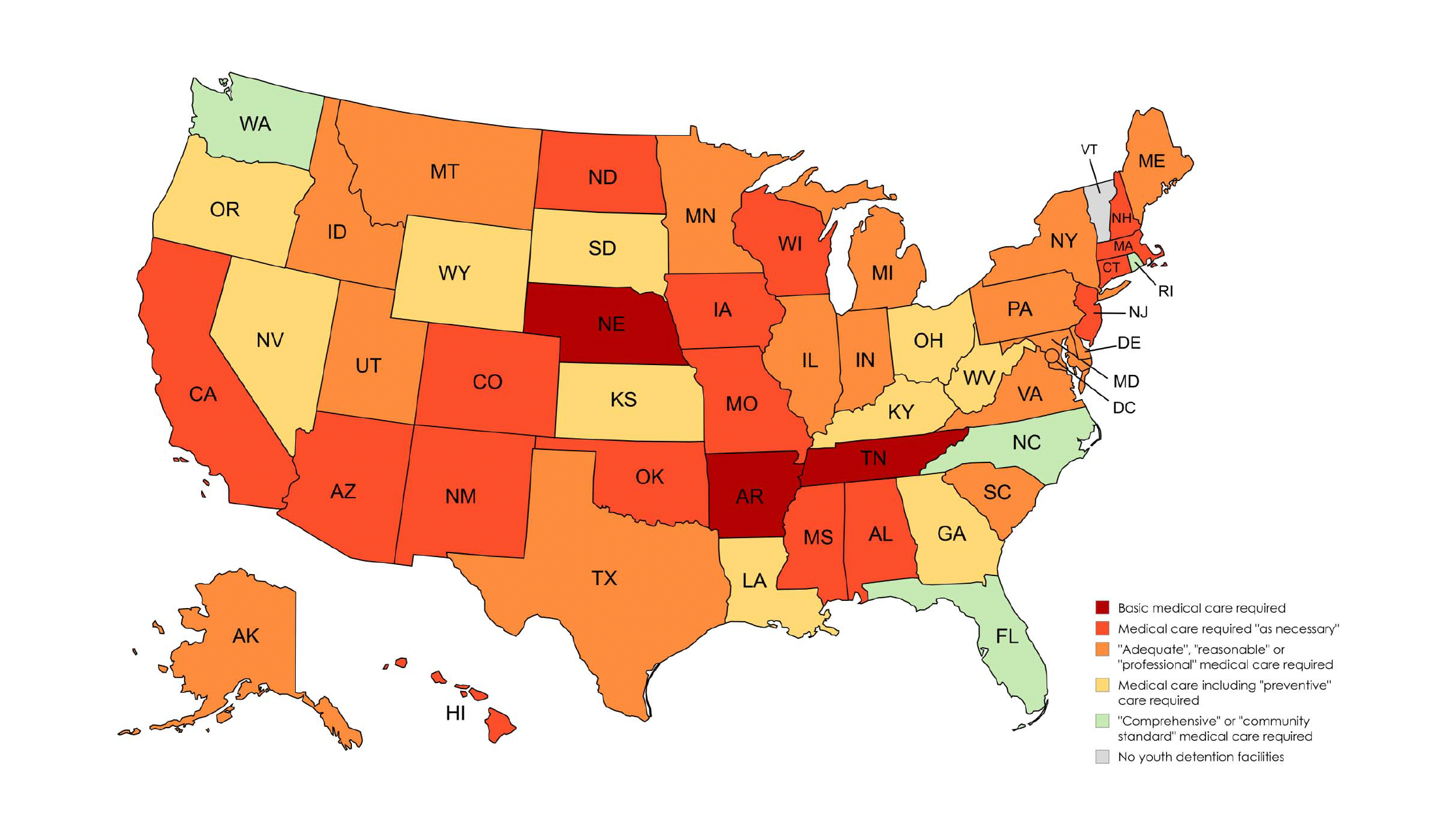

Our research reviewed U.S. state laws, administrative code, and policies that set minimum standards for medical care in youth confinement facilities across 50 U.S. States and the District of Columbia. We found striking differences and gaps in standards: only four states require a comprehensive or community standard of care. Most states fall into middle tiers with vague requirements, such as “adequate care” or care “as necessary,” and no explicit commitment to preventive services. Three states have the lowest tier, requiring only “basic” care or setting no standard at all.

FIGURE 1. Minimum standards for medical care for incarcerated youth across the United States.

Notably, the standards requiring the most robust care are generally found in policy or administrative code rather than state law, making them easier to weaken, remove, or even erase at the whim of an agency administrator. The inconsistency in standards is particularly concerning given recent Medicaid reforms that create opportunities for states to expand health and re-entry services for young people in detention.[3] These reforms risk being inconsistently implemented or ignored without binding legal standards and independent oversight.

Based on our findings, we developed model legislation requiring care to “meet or exceed” community standards. We recommended that this include urgent, preventive, and continuous healthcare services, reference up-to-date pediatric guidelines and ensure that monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are in place. Building on these recommendations, CFJJ recently supported the introduction of legislation in Massachusetts by Rep. Greg Schwartz (H.285) and Sen. Jacob Oliviera (S.169). This legislation would set the healthcare standard for children and youth in Department of Youth Services custody to “meet or exceed” the current pediatric community standard, including preventive care, health promotion, and continuity of care before, during and after release.[4]

Our research underscores that while preventing youth incarceration must remain the goal, it is essential, where youth are incarcerated, to provide care that not only meets but exceeds community standards. This can ensure that, while in custody, youth benefit from efforts to address long-standing health inequities, rather than seeing those inequities widen, as remains the case at present. I am deeply grateful to the FXB Center for supporting this work, and hope that it can inspire further advocacy and research in this crucial area.

[The above represents solely my own views and does not necessarily represent the views of the institution.]

[1] Borschmann, R., et al. (2020). The health of adolescents in detention: A global scoping review. The Lancet Public Health, 5(2), e114–e126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30217-8

[2] Braverman, P., & Murray, P. J.; Committee on Adolescence. (2011). Health care for youth in the juvenile justice system. Pediatrics, 128(6), 1219–1235. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1757

[3] Health and Reentry Project. (2025, July). Medicaid’s role in advancing reentry: Key policies. https://healthandreentryproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Harp-MedicaidReentry-July2025.pdf

[4] Citizens for Juvenile Justice. (2025). Fact Sheet https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58ea378e414fb5fae5ba06c7/t/681d514737e0e47931e865e2/1746751816157/FACT+SHEET+Health+Standards.pdf