The one resource Boston cannot afford to discard

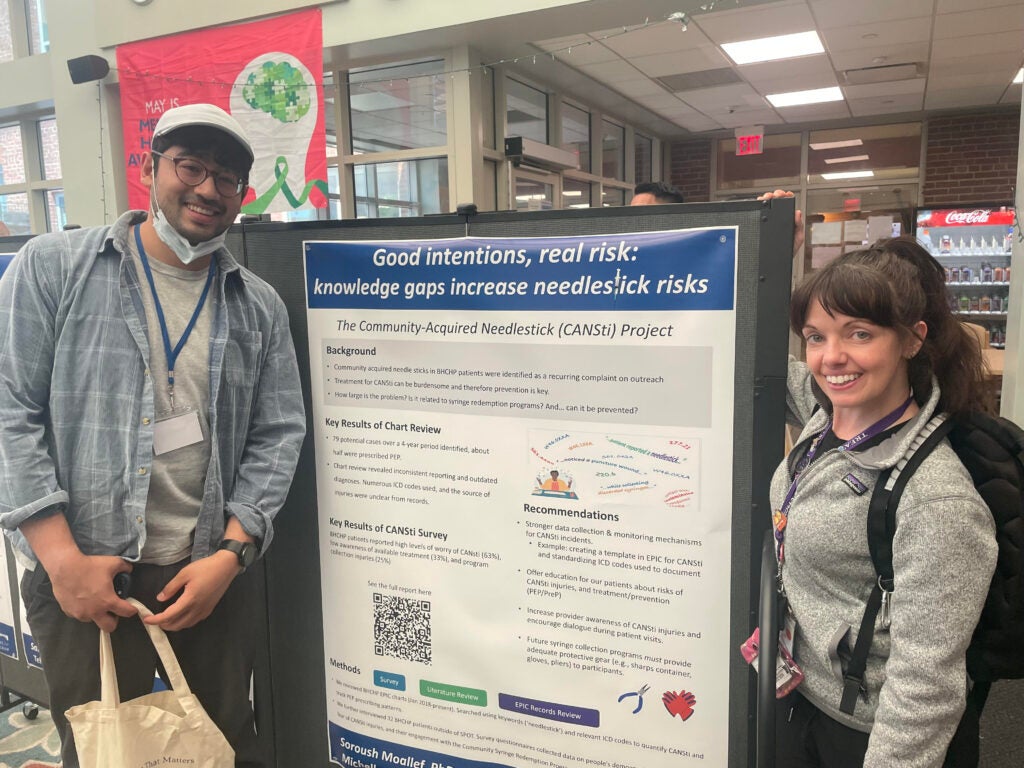

Soroush Moallef, MHS, joined the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) as an intern through the FXB Racial Justice Program in 2023, 2024, and again in 2025. These extended placements allowed him to complete the community‑acquired needlestick (CANSTI) project, including the evaluation of medical records, administration of surveys with BHCHP patients, and the development and write‑up of a public health report that incorporated a literature review. Soroush is a Population Health Sciences PhD candidate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, specializing in social and spatial epidemiology within the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Michelle (Misch) Whitaker, RN, CARN is the nurse manager of SPOT at BHCHP. SPOT (Supportive Place for Observation and Treatment) staff provide medical monitoring for the prevention of opioid overdoses, as well as wound care, referrals to MOUD, PrEP, direct observation therapy (DOT) and other services that promote the health and safety of people who use drugs. Her role also includes staff trainings on compassionate overdose response guidelines and best practices for how healthcare providers can reduce the risks associated with substance use for some of the program’s most complex and vulnerable patients.

By Soroush Moallef, MHS, and Michelle (Misch) Whitaker, RN, CARN

In 2020, a city-funded program in Boston offered a seemingly simple solution to a visible problem: it paid twenty cents for every discarded syringe turned in around the Mass & Cass neighborhood. On paper, it had reportedly reduced 311 calls in Boston for discarded syringes by half. But as we began our fieldwork there in June 2023— Soroush as an FXB Center intern at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) and Michelle the nurse supervisor of the Supportive Place for Observation and Treatment at BHCHP, our interviews with 32 BHCHP patients told a different story. We learned that the program was inadvertently creating a hidden risk. Patients, collecting syringes for the program without the gloves, tongs, or safety gear issued to municipal crews, were reporting being inadvertently stuck. It was a stark introduction to a pattern we would witness all summer: policy that addresses a visible symptom while creating an invisible injury.

Then, over the single ten-week span of that same internship, the neighborhood’s wider care infrastructure fell away in real time. Mass & Cass, long the epicenter of a humanitarian crisis of substance use, homelessness, and structural neglect, lost critical pillars of care in rapid succession. The Roundhouse Hotel, repurposed as crisis housing and medical-stabilization beds, closed. The Boston Public Health Commission’s Engagement Center, a low threshold refuge offering showers, food, internet, medical care, and community to more than 300 people a day, shuttered. Almost simultaneously, police forcibly cleared the Atkinson Street encampment, replacing tents with cruisers and concrete barriers. A philosophy of engagement was displaced by a logic of enforcement.

When funding for the syringe-redemption program lapsed in June of 2024, the vans vanished too, eliminating an important—if flawed—mechanism for disposal. Our interviews revealed that many patients relied on the redemption program as a source of income. The consequences were predictable: 311 complaints about discarded syringes rose, with calls originating far beyond the few blocks once ring-fenced as Mass & Cass. A vocal city councilor and several neighborhood groups now cite that uptick as proof the area is “out of control,” pressing for a zero-tolerance crackdown, an end to sterile-syringe distribution, and even deployment of the National Guard.

This political narrative deliberately omits the context our work provides. For years, the city had relied on a program that transferred the risk of hazardous waste collection onto its most vulnerable residents. When that program’s funding lapsed at the same time other low-threshold services were being closed and encampment sweeps took place, the result was a foreseeable public health crisis that disconnected a community of people from a constellation of life-saving services aimed at supporting recovery and transitions to housing.

Now, in a troubling irony, the city is reinstating the redemption program to manage the fallout, poised to repeat the cycle of addressing a visible problem while ignoring the hidden human cost. Holding a displaced community responsible for the consequences of budget decisions is not policy—it is scapegoating.

A better path remains, one that starts not with enforcement, but with compassionate infrastructure. Reopening hubs like the Engagement Center would reconnect people to medical care, food, housing referrals, and basic dignity through a single doorway. Enforcement cannot fill the voids left by closed clinics, and policy should be guided by evidence of what works, not by the volume of 311 complaints.

Our work was a stark lesson in how quickly policy debates can ignore lived reality. We are grateful to the FXB Center for the mentorship and support that allowed this work to happen, and especially to the BHCHP patients who shared their experiences.

The most critical data we gathered—the stories of injury, lost income, and worry—came from their expertise. It is the evidence that should guide us, and the one resource Boston cannot afford to discard.

[The above represents solely the views of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the institution.]